In light of the still-ongoing controversy regarding LGBT groups’ efforts to march in Boston’s St. Patrick’s day parade, I’d like to revisit the 1995 Supreme Court case that upheld the parade organizers’ right to exclude such groups.

The St. Patrick’s day parade has a long history in Boston. The City of Boston was the official sponsor of the parade until 1947, at which point Mayor Curley granted authority over the parade to the South Boston Allied Veterans War Council, a group of individuals from various South Boston veterans groups. Nonetheless, the City continued to fund the parade, and allowed parade organizers to use the City seal until 1992.

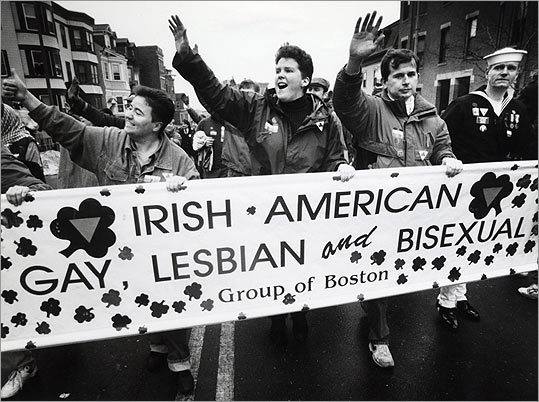

In 1992, a group of Boston residents formed the Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston (GLIB). Although GLIB was denied permission to march in the 1992 parade, it obtained a court order from famed Judge Hiller Zobel allowing it to do so. GLIB members marched through the streets of Southie in the 1992 and 1993 parades, escorted by riot police, all the while subject to vicious insults, hurled beer bottles, and general nastiness. Due to the uproar, the parade organizers decided to scrap the 1994 parade altogether. By the time the parade returned to the streets in 1995, the organizers had won a decisive victory at the Supreme Court.

Before we get to the Supreme Court’s ruling, it is important to understand the rationale behind Massachusetts state courts’ rulings that GLIB was entitled to participate in the parade. The Superior Court, which heard the case initially, based its ruling on the Massachusetts Public Accommodations Law. In its current iteration, this law “prohibits making any distinction, discrimination, or restriction in admission to or treatment in a place of public accommodation based on religion, creed, class, race, color, denomination, sex, sexual orientation, nationality, or because of deafness or blindness, or any physical or mental disability.” The court rejected the parade organizers’ argument that the parade was a private event, instead classifying it as an “open recreational event” therefore subject to the Commonwealth’s public accommodations laws. This state’s highest court, the Supreme Judicial Court, agreed, affirming GLIB’s right to march.

As a brief aside, when this case reached the Supreme Court, the Justices noted that Massachusetts’ public accommodations laws had a “venerable history.” These laws arose from English common law, which prohibited discrimination by innkeepers and blacksmiths; after the Civil War, Massachusetts became the first state to explicitly prohibit such discrimination based on race. As society evolved, the number of protected categories grew; activists are currently attempting to get “gender identity” added to the list to ensure the protection of transgender individuals.

The case reached the Supreme Court in 1995. The Court began its analysis with a look at parades, and the broader social function they serve. Quoting a treatise on street theater in 19th-century Philadelphia, the Court noted that: “Parades are public dramas of social relations, and in them performers define who can be a social actor and what subjects and ideas are available for communication and consideration.”

The Court thus defined “parade” to indicate marchers who were making “some sort of collective point.” Regardless of whether the “collective point” of a parade was narrow or broad, the Court held that the act of making that point was a form of expression entitled to protection under the First Amendment.

Once the Court established that the parade itself was a form of expressive activity, it was easily able to find that the organizers had the right to exclude messages with which it did not agree. The Court found that the case “boil

The parade organizers thus had the right to select which groups, or units, could march in the parade. The inclusion of a particular unit in the parade would suggest that the organizers supported that unit’s message; conversely, the exclusion of a particular group would reflect the organizers’ rejection of that group’s message.

The Court held that Commonwealth’s public accommodations law could not be applied to expressive activity, as it would, in effect, “require speakers to modify the content of their expression to whatever extent beneficiaries of the law choose to alter it with messages of their own.”

The Court concluded by stating that the Commonwealth had no business “promoting an approved message or discouraging a disfavored one, however enlightened either purpose may strike the government.” The prior state court rulings could not stand, as they unconstitutionally forced the parade organizers to “alter the expressive content of their parade.”

And so it is. Our former Mayor, Thomas Menino boycotted the parade from 1994 until his retirement last year. Our current Mayor, Marty Walsh, intends to do so unless and until parade organizers relent and allow LGBT groups to march openly. John “Wacko” Hurley, the parade’s organizer, had his day in the Supreme Court and won; the position he espouses towards his LGBT brethren, however, is now, more than ever, a loser.

Sources:

Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, 115 S.Ct. 2338

Boston Globe Archives

Massachusetts Public Accommodation Law (M.G.L c. 272, s. 92A, 98 and 98A)